From the What on Earth programme on the CBC News website, Hannah Ritchie provides data to show where we are on the road to sustainability.

The road to sustainability can seem hazy. Data shows where we need to go

“Don’t solar panels and wind turbines generate huge amounts of waste? Aren’t our efforts pointless if China’s emissions keep growing?”

Those are but a few of the questions people regularly ask Hannah Ritchie, a data scientist and the deputy editor of Our World in Data.

“There is this feeling that, in order to tackle climate change, we’ll be creating huge numbers of other massive problems,” Ritchie said.

Sometimes these objections can be weaponized as arguments against the green energy transition. On other occasions, this conflicting information comes from climate-conscious sources who don’t have the full picture, Ritchie says.

But how big are these problems, really? And, more importantly, are they worse than climate change itself?

In her new book, Clearing the Air: A Hopeful Guide to Solving Climate Change in 50 Questions and Answers, Ritchie uses data to put those concerns in context.

We spoke to Ritchie and dug deeper on a few of those questions.

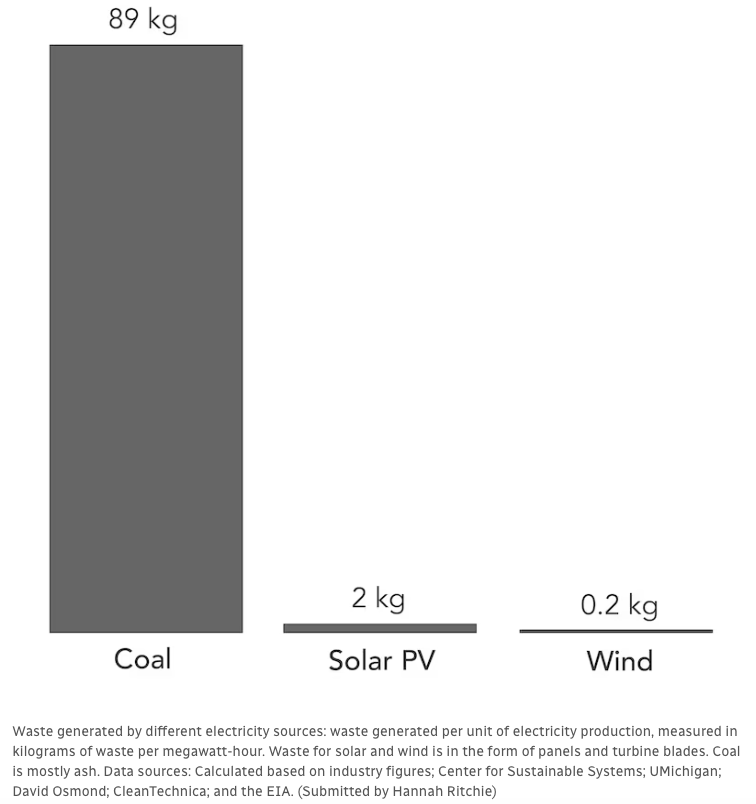

Don’t solar panels and wind turbines generate huge amounts of waste?

Solar panels and wind blades, when they reach the end of their lifespan, become waste if they’re not recycled.

“You’ll often get, on social media, some picture of wind turbines dumped in a field or solar panels maybe dumped somewhere,” Ritchie said.

That has sparked concern that a renewable technology boom equates a boom in renewable technology garbage.

But when you put the numbers in context, the picture is clear: waste from green energy sources is better than the alternative.

For example, when you burn coal, the leftover product becomes coal ash. Breaking down the data, Ritchie shows that coal generates 50 times more waste than solar power — and 500 times more than wind.

Coal ash is also highly toxic. In the United States, some power plants may dispose of coal ash in surface ponds or landfills, or discharge it in waterways.

Plus, the renewable energy waste problem may be solvable. Most parts of solar panels can be recycled, though countries need to invest in an efficient recycling system to make this happen.

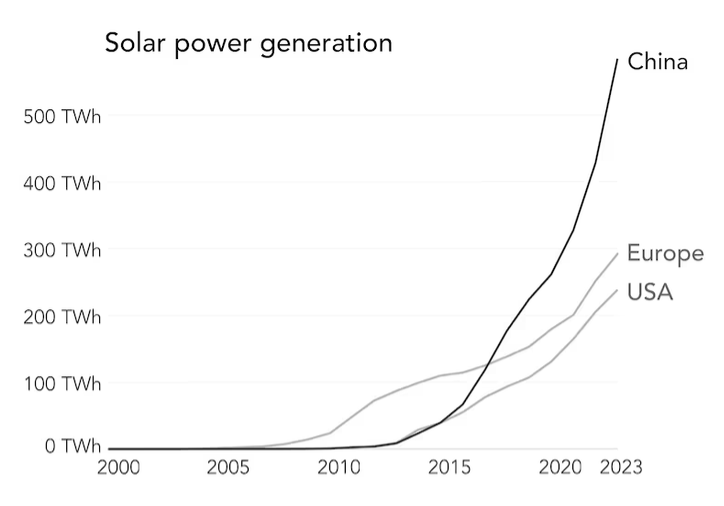

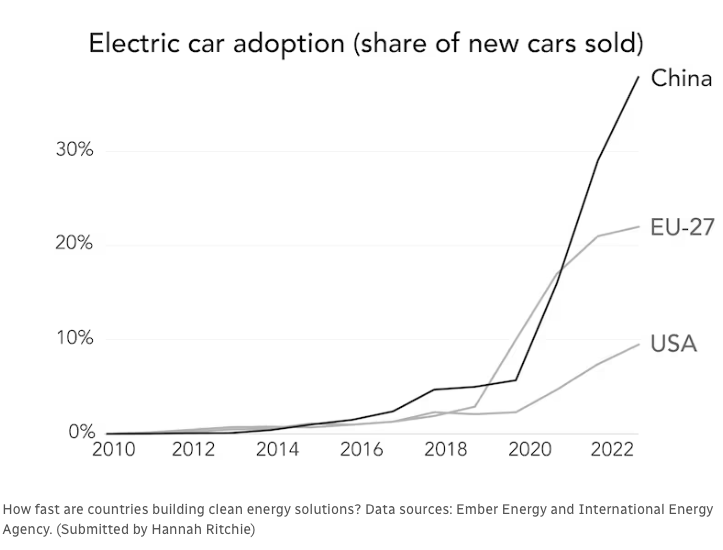

Aren’t our efforts pointless if China’s emissions keep growing?

This can be answered with some good news: China’s emissions may have already stopped growing.

“China has been going extremely quickly on deployment of clean power, the rollout of electric vehicles,” Ritchie said.

On top of that, the country’s green technology investment — boosted by tumbling production prices — is spreading across the world.

“Over the past year, you’ve actually seen a huge boom in the imports of solar panels in Pakistan,” said Ritchie. In Brazil, sub-Saharan Africa and other parts that make up the Global South, people are hungry for clean, cheap power, she says, and electrification is trending upwards.

Importantly, Ritchie notes, China’s emissions have recently plateaued, and there are reasons to believe they could start to go down this year.

“Because it’s the world’s largest emitter,” she said, “it would likely be the case that if China’s emissions dropped, global emissions would also drop.”

How can we make better choices?

Ritchie is concerned that we become despondent when we believe there are no good choices — when, in reality, some of those choices could help both the climate and ourselves.

Electrification, for example, offers co-benefits that aren’t talked about enough, Ritchie points out.

“Driving an electric car uses about a third of the energy of driving a petrol or diesel one,” said Ritchie.

That’s because in an EV, the vast majority of the energy in the battery is used to propel the car. In a gasoline car, it’s the opposite — only about 20 per cent is converted into movement, while the rest is lost as heat. In the same way, renewable energy power plants are much more efficient than fossil fuel power plants.

“You have these huge efficiency benefits where you can also get cost benefits,” she said.

The potential for cost savings, in other words, are significant. From travel to heating and air conditioning, “we could have exactly the amount of energy services that we have now or more — but using a fraction of the energy,” she said.

“And that’s purely through this process of electrification and investing in more efficient energy technologies.”

External link