This briefing by the European Environment Agency provides information about the interlinkages between circular economy and climate change mitigation. It is based on a literature review of recent modelling results and supports the 2025 Clean Industrial Deal and 2020 Circular Economy Action Plan.

Assessing the climate mitigation potential of circular economy

Key messages

Over the past five years more than 130 articles have been published documenting the significant climate mitigation potential of the circular economy.

However, methodological differences across studies make direct comparison of results challenging, yet some general highlights can be made.

Based on an average of the estimates for reductions across the studies, the circular economy could deliver a reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of 33%, yet this ranges from 2% to 99%.

Results from individual sectors, indicate that emissions from waste management could be reduced by an average of 52% (range: 9-88%); from construction by 48% (range: 15-99%); and from industry by 26% (range: 5-61%).

Smaller living spaces, dietary shifts and shared mobility are commonly cited in modelling exercises as individual measures with high mitigation potential.

Further work is needed to integrate circular economy measures into climate change scenarios and to develop modelling tools that support policymakers in assessing their potential benefits.

Introduction

There is growing awareness of the key role that the circular economy can play in reducing GHG emissions (EC, 2024). In order to achieve global climate targets, the use of materials, in addition to energy, must be addressed (EMF, 2019; UNEP IRP, 2024).

This recognition is reflected politically through key messages highlighting the interlinkages between the circular economy and climate change mitigation at both the European and global levels. Examples can be found in the 2025 Clean Industrial Deal, the 2020 Circular Economy Action Plan, the 2022 UN Environment Assembly Resolution 5/11 and the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report.

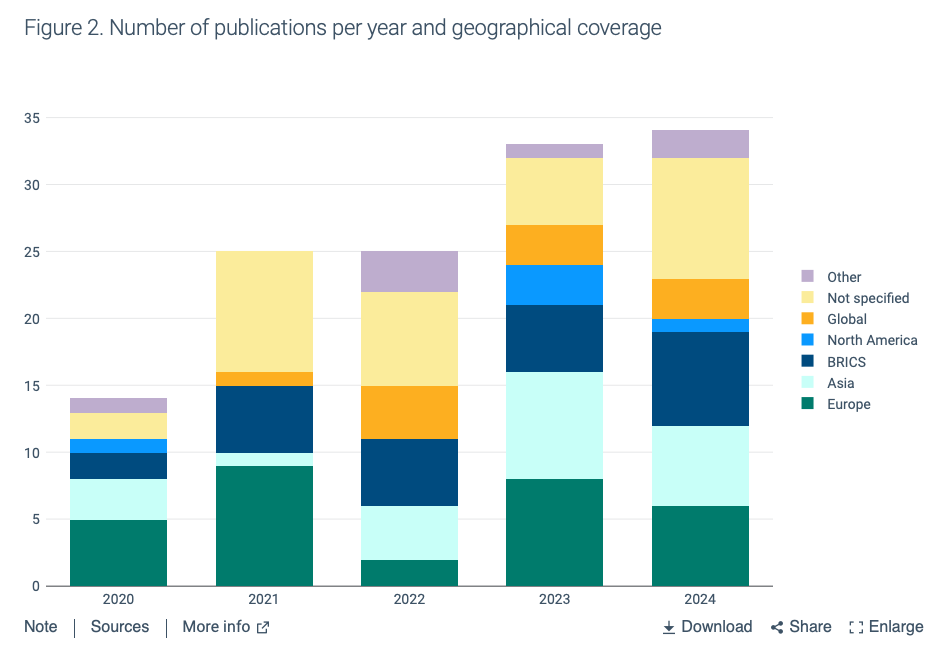

There has also been a marked increase in the number of publications exploring this connection (Figure 2) (Cantzler et al., 2020; Circle Economy, 2021; ETC CE, 2025; Wiedenhofer et al., 2025). This recent surge in research and political attention makes it a timely moment to take stock of the existing findings and assess the climate mitigation potential of circular economy actions.

This briefing is based on the 2026 technical report Climate mitigation contributions from circular economy actions by the European Topic Centre on Circular Economy and Resource Efficiency (ETC CE). The report initially identified over 460 articles on this topic, published between 2020 and March 2025. After applying several filters — including for quantifiable results, methodological robustness and minimum citation thresholds — the list was narrowed to 131 publications. These were then analysed in depth.

Building on this review, this briefing assesses the recent literature quantifying the potential for GHG reductions from circular economy actions. It provides a consolidated overview of how circular approaches contribute to climate mitigation, highlighting hotspots where the potential is greatest.

A key finding is that estimates of mitigation potential vary widely across studies. The briefing therefore also explores the underlying reasons for these differences and outlines key considerations for interpreting this body of research.

How the circular economy can reduce GHG emissions

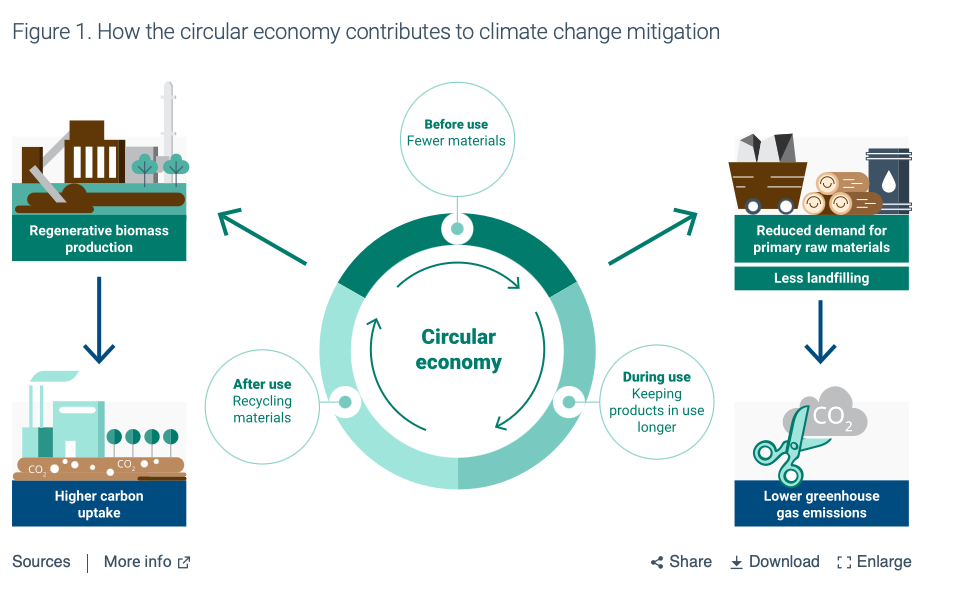

The circular economy can lower demand for primary raw materials throughout the product value chain (EEA, 2024b) and thereby reduce emissions associated with their extraction and processing (Figure 1).

- Before use: measures such as circular design and sustainable material selection can minimise the resource inputs required and facilitate reuse or recycling later in the cycle.

- During use: actions that extend product lifetimes — through repair, refurbishment or shared use — can further reduce demand for new materials by keeping materials in active use for longer.

- After use: when products and materials have been discarded, recycling and retaining materials help to close the loop and decrease reliance on primary resource extraction. Reducing the amount of waste sent to landfill lowers methane emissions generated during waste decomposition.

Together, these measures can significantly cut emissions from extracting and processing raw materials — which account for about 55% of global GHG emissions, including emissions linked to the production of food or fossil fuels (UNEP IRP, 2024).

Circular approaches can also support more sustainable production and sourcing activities, particularly in biomass systems; improved land management and regenerative agricultural practices can both reduce emissions and enhance carbon sequestration (EMF, 2021).

Literature on the climate mitigation potential of the circular economy

Of the 131 publications reviewed (2020-March 2025):

- 14 were published in 2020 compared with 34 in 2024 (Figure 2);

- most studies focused on developed countries, particularly Europe (30 studies);

- 24 studies examined the so-called BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), with the majority of these focusing on China;

- 11 studies took a global perspective.

These findings demonstrate a growing research interest in the link between the circular economy and climate change. They also indicate that the circular economy debate extends beyond Europe, attracting attention across diverse regions and economic contexts.

The reviewed literature employs a range of analytical methods. Nearly half (48%) use Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) as the primary approach. Hybrid approaches combining multiple methods are used in 32% of the studies, 10% are meta-studies, Material Flow Analysis (MFA) is used in 4% and Environmentally Extended Input-Output (EEIO) analysis in 3%.

Different methods capture different aspects of circular economy impacts (e.g. LCA provides detailed insights into the mitigation potential of specific circular actions but is less suited to assessing the interactions of circular economy actions across different sectors or the economy-wide effects). A detailed overview of what can be captured by the various methods can be found in ETC CE (2024) and Wiedenhofer et al. (2025).

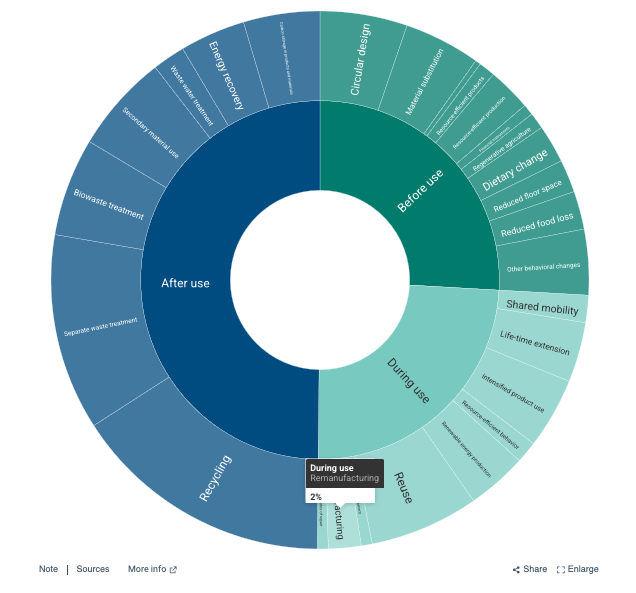

The scope of circular economy measures also varies considerably across the studies. For example, there are discrepancies in terms of what types of measures are included as part of the circular economy. Additionally, the articles address measures across the life cycle but there is uneven coverage of the different stages (EEA, 2024a) (Figure 3):

- before use (e.g. material substitution, circular design, lightweighting): 26% of studies;

- during use (e.g. reuse, product life extension): 24%;

- after use (e.g. waste management, recycling): 50%.

This pattern suggests that the mitigation potential of waste management measures is often a key focus. Meanwhile, the potential of circular strategies during the before and the use phase remains under-explored and could benefit from further assessment.

Figure 3. Circular economy measures modelled in the literature reviewed

Assessment of the circular economy global climate mitigation potential

In order to make the results of the reviewed publications easier to compare, they were converted into two distinct categories described below.

- Relative emission reductions: expressed as percentage GHG emission reductions for a specific sector or circular economy measure and estimated in comparison to a business as usual (BAU) baseline with the range of results across studies also given. For example, waste management: 52% (range: 9-88%) means that, compared to current waste management systems, the averaged estimate for GHG emission reductions from circular economy measures in the waste management sector across all studies is 52% (with studies estimating a range of reductions from 9-88%).

- Absolute emission reductions: estimated GHG emission reductions for a sector or circular economy measure from a base year (e.g. 2025) up to 2050 in comparison to BAU and expressed in giga tonnes of CO2 equivalent (Gt CO2e). For example, agriculture and food systems: 7.3 Gt CO2e in 2050 means that circular economy measures could potentially result in 7.3 Gt CO2e less GHG emissions in that sector by 2050 compared to a BAU scenario. Assessment of absolute emission reductions was could only be carried out for studies with a global and economy-wide scope (n=13).

The studies include a wide range of estimates of figures for reduction potential, from 2% to 99% (c.f. Cantzler et al., 2020; Gallego-Schmid et al., 2020; Wiedenhofer et al., 2025). When aggregated, the reviewed literature suggests a global average potential reduction of around 33%. However, it is important to note that this represents a theoretical estimate — an indication of the significant role circular economy measures could play rather than an exact prediction of achievable reductions.

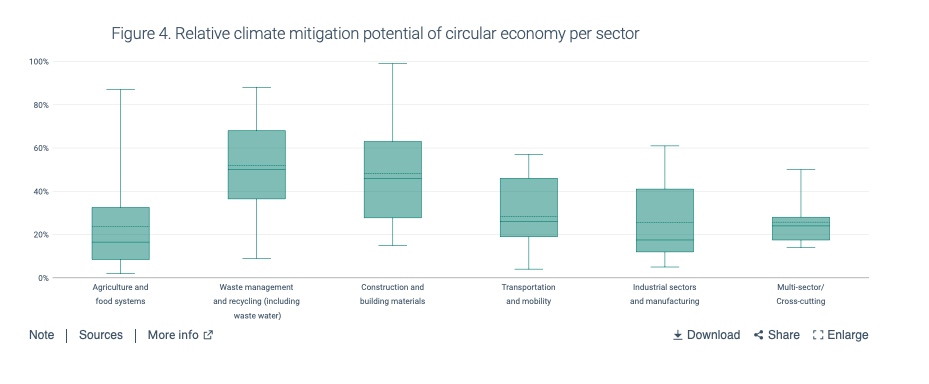

When assessing the mitigation potential in various sectors, the review indicates that waste management offers the highest relative climate mitigation potential, averaging at 52% (range: 9-88%). This is followed by (see Figure 4):

- construction and buildings: 48% (range: 15-99%);

- transport and mobility: 28% (range: 4-57%);

- industry: 26% (range: 5-61%);

- agriculture: 24% (range 2-87%).

The picture is slightly different when the circular economy mitigation potential in these sectors is presented in terms of absolute GHG emission reductions. Here, agriculture and food systems has the highest global potential for reductions — up to 7.3 Gt CO2e in 2050.

However, within this category the estimates for the climate mitigation potential of circular economy measures vary significantly. For example, ‘dietary shifts’ represents a circular economy action with significant potential (albeit not all studies include it as a circular economy measure). However, the studies have different ambition levels, e.g. different assumptions about the extent to which our diets can switch from animal-based food to plant-based food. This means that estimated mitigation potentials differ by a factor of six (0.9-5.9 Gt CO2e) between studies (c.f. Creutzig et al., 2022; Steinitz et al., 2024).

The construction and buildings category has the second-highest global potential for reductions; circular measures could achieve savings of up to 6.8 Gt CO2e globally by 2050, primarily through reducing demand for floor space and substituting high-emission materials (IPCC, 2022; UNEP IRP, 2024; Pauliuk et al., 2024; Circle Economy, 2021).

When comparing the relative (percentage change) GHG emission reductions with absolute (or total) emission reductions across different sectors we see that while waste management has the highest relative potential for reductions, it has among the lowest potentials for absolute reductions. This could indicate a lower emissions intensity in this sector compared to other sectors (ETC CE, 2025).

Considering total climate mitigation potential in tonnes of GHG emissions, the studies indicate that circular economy measures in the agriculture and food systems sector can deliver the highest potential, followed by construction and buildings and then the transport and mobility sector.

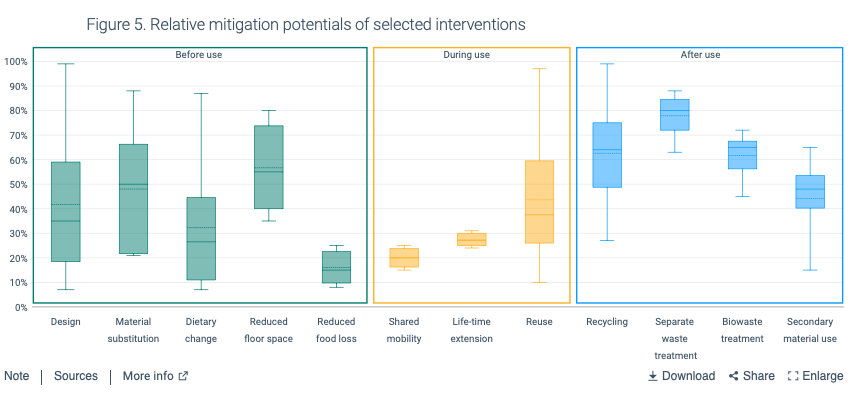

Figure 5 provides an overview of individual circular economy measures across the life cycle. These are grouped into the following three categories: before use, during use and after use (EEA, 2024a).

Similarly to the sectoral perspective, the life-cycle perspective shows that the highest relative reduction potential is during the after-use stage, with an average reduction of around 60%. The studies point to measures including recycling (potential to reduce emissions by 63%) and separate waste treatment (78%) as being particularly effective.

Measures during the before-use phase also indicate substantial opportunities (potential to reduce emissions by 39%). The studies highlight material substitution (48%) and circular design (42%) as particularly promising.

Actions taken during the use phase, such as reuse and product life extension, show a comparable average reduction potential of 40%. Reuse was the most frequently studied measure.

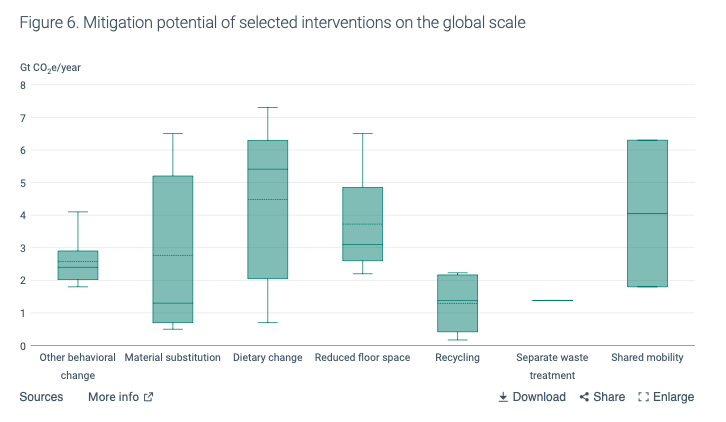

Figure 6 illustrates the absolute mitigation potential of circular economy measures identified in studies with a global focus (n=13). As noted in the sectoral analysis, interventions such as reducing floor space, increasing the lifetime of new buildings and material substitution together could yield 2.2 Gt CO2e of global emission reductions by 2050 (UNEP IRP, 2024).

Meanwhile, shifting diets could reduce GHG emissions by 6 Gt CO2e by 2050 if all countries adopt an almost purely vegetarian diet (Steinitz et al., 2024). Switching to regenerative agriculture approaches could further reduce global emissions by 2.5 Gt CO2e by 2050 (EMF, 2021).

There are also indications in the reviewed literature that behavioural change measures — including shared mobility and sustainable consumption (Circle Economy, 2021; Creutzig et al., 2022; UNEP IRP, 2024) — deliver greater mitigation potential than purely ‘technical solutions’ such as recycling (Gorman et al., 2022) or separate waste treatment (Gómez-Sanabria et al., 2022).

Indeed, several studies suggest that demand-side measures, which influence consumption patterns and material demand, offer particularly high mitigation potential. However, given the relatively small number of globally focused studies (n=13), it is not possible to rule out bias towards specific measures. Consequently, the selection of measures in the relative and absolute assessments of potential GHG reductions is not fully aligned and a direct comparison cannot be made.

Another notable feature of the literature review is the wide disparity in results: in nearly all the categories, the highest mitigation potential estimate is over three times higher than the lowest estimate. This underscores the challenges of comparing studies that employ different methodological approaches, assumptions and levels of detail.

Lessons learned on the climate mitigation potential of the circular economy

Over the past 5 years, the scientific literature has established solid evidence for the climate mitigation potential of the circular economy. Clear synergies have been identified between circular economy measures, energy efficiency and the de-fossilisation of the economy.

The positive contribution of circular strategies to climate mitigation has been clearly demonstrated; however, the wide variation in results across studies makes it difficult to define a single, concrete estimate for mitigation potential. Instead, the recent studies on the circular economy and GHG reductions point to some key lessons.

Improved waste management is low-hanging fruit

Circular economy measures, such as minimising landfill and separating organic waste, can serve as entry points for countries beginning their circular transition. These actions not only enhance resource efficiency but also have considerable potential to reduce GHG emissions (ETC CE, 2024). However, to fully realise the benefits of the circular economy, upstream measures — in the areas of product design, reuse and material substitution — must also be included.

The construction and buildings sector offers key opportunities for climate mitigation

The construction and buildings sector offers some of the largest opportunities for circular economy climate mitigation due to its high material use. Globally, buildings account for nearly half of all material use (UNEP, 2020). This means that circular measures in this sector have high leverage. Both production-side actions (e.g. low-carbon materials, modular design) and consumption-side measures (e.g. reducing floor space per capita, increasing use intensity) can lower the demand for new construction and contribute to substantial GHG reductions (EEA, 2024c). Furthermore, the use of bio-based construction materials can enable the temporary storage of carbon in harvested wood products, thereby functioning as a temporary carbon sink (EC and Viegand Maagøe, 2025).

The focus should be on climate-intensive materials

Not all materials contribute equally to GHG emissions. Metals and other carbon-intensive raw materials generate far higher emissions than non-metallic minerals when considering the extraction and processing of raw materials phase (ETC CE, 2025). Targeting these materials through recycling, reuse and substitution (e.g. through less CO2-intensive or bio-based materials) can therefore yield significant climate benefits (EC, 2025).

Combining upstream and downstream measures offers the greatest mitigation potential

Downstream measures are somewhat ‘over-represented’ in the literature, while upstream measures — including eco-design, reuse and repair — and demand-side measures are overlooked. All measures have significant potential for mitigation on their own; however, a combination of upstream and downstream measures as well as technological innovations and behavioural changes will foster the greatest possible reduction in global material demand and GHG emissions (IPCC, 2022; Circle Economy, 2021; ETC CE, 2025). To complement this, it is important to accurately quantify the biogenic carbon storage.

Methodological transparency is crucial

The results of studies in this area are all significantly influenced by their choice of analytical method (e.g. LCA, MFA, EEIO), assumptions, timelines, baselines, circularity scope and geographical coverage. These variations mean that studies are often not directly comparable. They also mean that no single study can necessarily be considered more ‘accurate’ than another. Consequently, it is essential that studies are transparent in documenting how their results have been generated and in pinpointing what they represent.

Various tools are available for calculating the climate mitigation potential of the circular economy

While methodological differences among studies will always exist, there is significant potential to improve comparability by adopting consistent analytical frameworks. Comparing results from studies using the same methodological frameworks could help — e.g. the ETC CE’s Measuring environmental benefits of Circular Economy (2025) and the Joint Research Centre’s (JRC) work on assessing the mitigation potential of heavy industry (JRC, 2025); so too could efforts towards harmonising impact factors for circular economy measures and reducing data gaps.

In addition, several Horizon Europe projects — including CircEUlar, CIRCOMOD and CO2NSTRUCT — are developing comprehensive modelling frameworks that are better designed to quantify the climate mitigation potential of circular economy measures. Furthermore, beyond the emission reductions included in the mitigation potential, it is essential to accurately quantify biogenic carbon storage.

External link