The shipping sector is now the first industry with internationally mandated targets to reduce emissions. This outcome is the result of constructive discussions among IMO member states since the adoption of the IMO’s 2023 greenhouse gas (GHG) strategy. Ship owners who fail to reduce emissions intensity 30% by 2035 will have to pay into a “net zero fund” to clean up shipping through green fuels. In an article on the Climate Home News, Joe Lo discusses latest developments. It should be added that the Financial Times reported earlier this week that the US has threatened to retaliate against any international levy on ships.

Governments agree green shipping targets and fees for missing them

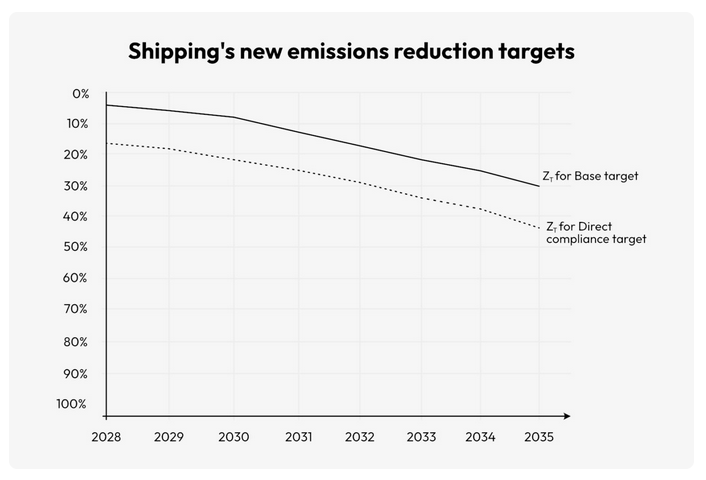

Governments at the International Maritime Organization (IMO) have agreed on a set of annual emissions reduction targets for 2028 to 2035 along with financial penalties for failing to meet them.

After a week of talks in London, they voted through a decision that ship owners should reduce the emissions intensity of their vessels – the amount of climate-heating emissions per unit of fuel – by 30% by 2035 and 65% by 2040, both against 2008 levels.

In a contentious closing session on Friday, where some large fossil fuel nations opposed the measures, they also fixed annual targets for each year between 2028 and 2035. Targets for the 2035-2040 period will be decided in 2032.

Governments already agreed back in 2023 to reach net zero “by or around i.e. close to 2050” – and this week’s talks were key to working out how to get there by adopting greener fuels and energy efficiency.

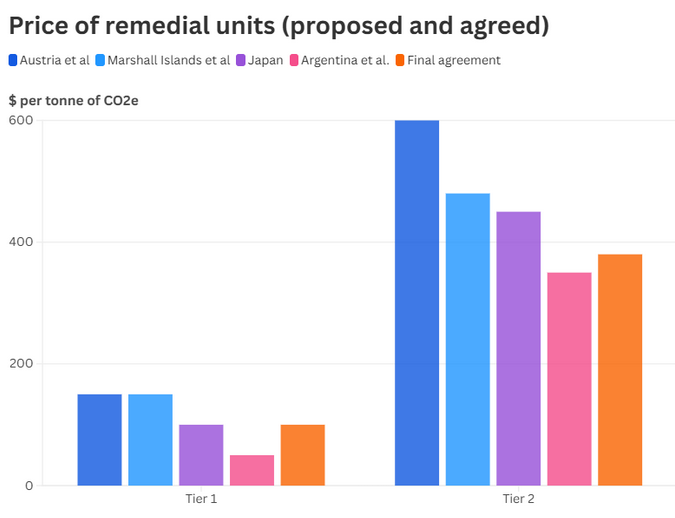

Ship owners who fail to meet the “base” targets on the path to achieving a 30% reduction by 2035 will have to buy “remedial units” from the IMO to make up the difference, priced at $380 a tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent.

The IMO will spend the money through a new “Net Zero Fund” on cleaning up the maritime sector, helping workers through the green transition and compensating for any negative impacts of that transition on developing economies, such as increases in the price of food due to higher shipping costs.

No money raised from selling remedial units will be spent outside the maritime sector, disappointing climate activists and some governments which had hoped the money could generate tens of billions of dollars per year in broader climate finance.

On top of these base targets, governments have set additional compliance targets which are harder to meet and would deliver a more ambitious reduction in emissions intensity of 43% by 2035.

If shipowners fail to meet these additional goals, they can make up for it through three options: buying cheaper second-tier remedial units at $100 a tonne; buying “surplus units” from ships that have met the goals; or using surplus units they have banked by over-achieving in previous years.

Governments have also agreed on a threshold for how polluting a shipping fuel can be and still be officially considered a “zero or near zero fuel”, making its use eligible for funding from the Net Zero Fund.

That threshold has been set at 19 grammes of carbon dioxide equivalent per megajoule (gCO2e/MJ) of energy, falling to a maximum of 14 grammes in 2035. This sets up battles between industry and environmental lobbyists over the carbon intensity of different fuels, such as liquefied natural gas (LNG) and various types of biofuel.

The Society for Gas as a Marine Fuel, an industry group, argued in a paper submitted to the IMO that LNG has a carbon intensity of 17.4 gCO2e/MJ, whereas two others – Pacific Environment and the International Council on Clean Transportation – argue it is either 23.78 gCo2e/MJ or 27.95 gCo2e/MJ. Those higher measurements would make LNG ineligible for Net Zero Fund support.

Fossil fuel nations opposed

In the vote on the new measures at the IMO in London, 63 nations supported them, while 16 voted against and about 25 abstained. Those opposed were mainly nations whose economies rely on oil and gas – fossil fuels that currently power ships – like Saudi Arabia, Russia and Iran.

Explaining their opposition, the Saudi delegate said, “we believe in balance – achieving a balance between energy security and affordability, climate action and economic development”. His nation is “equally committed to all of these pillars and we understand that – in order to achieve progress – we must balance these priorities equally”, he added.

While some island nations supported the deal, a group of six abstained from the vote. Explaining their decision, Tuvalu’s transport minister Simon Kofe said the agreement was not ambitious enough and “lacks the necesssary incentives for industry to make the necessary shift to cleaner technologies”.

These and other island nations wanted a price on all shipping emissions from 2028 – and for that price to be at least $150 a tonne. On Monday, Marshall Islands ambassador Albon Ishoda warned reporters that his country and its allies would not support anything less than that.

On Friday, Kofe also expressed “disappointment” about how the deal was done, saying that small island developing states were not “adequately engaged in the formulation of this document”, which was “concerning”.

One nation that was not active at the talks was the United States, which has largely withdrawn from international environmental and climate processes under President Donald Trump, who supports the use of more fossil fuels.

Shipping news service Tradewinds reported that the US left the IMO talks on Tuesday night and threatened, in a letter sent to London-based embassies, “reciprocal measures so as to offset any fees charged to US ships” – although it is unclear what that might mean in practice.

External link

The maritime industry is far more important than the aviation industry, which makes this convenant particularly welcome. Achieving this has required a lot of determination, and a fair amount of compromise all round – including up until very recently, from the shipping interests in America.

Inevitably the tediousTrump blunderbuss has emerged at the end, suddenly threatening “reciprocal measures so as to offset any fees charged to US ships”. Hopefully the rest of the world will feel able to ignore such profound stupidity, marginalising the USA as the “rogue state” it is now fast becoming.

It has taken a long time to negotiate this agreement. I certainly hope the rest of the world will be able to ignore this bullying from the Trump administration. With the US trying to isolate itself, surely it will become less persuasive. Also, the latest draft budgets from the US show that the US will be providing significantly less money to international organisations should also reduce its global impact.