The EU’s Energy Performance of Buildings Directive gives considerable importance to consumers and the general public in knowing and understanding the energy performance of buildings. For public buildings, the idea was to have Display Energy Certificates (DECs) that would allow the public know the performance of buildings that were deemed part of the public space. Even with their growing pains, the DECs have been shown to be quite important in letting the public better follow the dynamics of energy consumption (i.e. has energy consumption for a specific government building dropped over time or increased?) Robert Cohen, from Verco Advisory Services and a friend of EiD, write on the twodegreesnetwork website about how the UK government is trying to have such certificates abolished. Why? Are they embarrassed by the lack of progress? Robert argues that the clear message here is that DECs can support a culture that prioritises energy efficiency. One would have thought this was what the government wanted. Surely some of you have views on this.

Should DECs be abolished … or improved?

The UK government has announced proposals that could see Display Energy Certificates for public buildings abolished. Are we in danger of throwing out the baby with the bath water asks Robert Cohen.

Two months before the last general election, the UK’s Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) issued a consultation on making better use of Display Energy Certificates (DECs) by extending them to all non-residential buildings. With uncanny symmetry of timing, three months in advance of the upcoming election, DCLG has just issued a new consultation on DECs, running to 11 March, this time seeking evidence on how the current regime could be streamlined and improved. It is arguably healthy to kick the tyres of any policy every five years or so. Even enthusiasts for DECs, such as myself, acknowledge there is much that could be done to reinvigorate them. Although somewhat unexpected, this consultation is therefore a welcome opportunity to rehearse whether DECs are worthwhile or “green tape”, and to collect the evidence to support the conclusions.

“Even enthusiasts for DECs, such as myself, acknowledge there is much that could be done to reinvigorate them.”

The wording of the consultation is robust, effectively stating that as DECs are not needed to comply with the EU Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), they therefore constitute ‘gold-plating’ and could be abolished altogether: all building energy certificate requirements in England and Wales could in principle be satisfied by the EPC, renewed every ten years.

The proposed streamlining (de-gold-plating) goes further than this: it anticipates exempting schools and universities from needing a DEC for any building that does not have an area of at least 500m2 ‘used as a community centre in the evenings on a daily basis’. To get legalistic, DCLG is stating (without seeking to consult on this point) that buildings failing this criterion are not “frequently visited by the public”, and therefore are not required by the EPBD to display an energy certificate. The other trigger for an existing building to get an energy certificate is when it is sold or let. Given that school and university buildings are rarely sold or let, DCLG effectively is adding these buildings to the list of those exempted by the EPBD from the energy certificate regime altogether. Like historical monuments and places of worship, they will not need an energy certificate, period – EPC, DEC, on display or not.

It can be argued that to do this would breach the spirit if not the letter of the EPBD. But this would also miss the point. If they are a form of gold-plating, it is reasonable for DCLG to seek evidence that underwrites the continuation of DECs, and how they might be improved. However, the consultation lacks suggestions for making the DEC regime more effective, strengthening its potentially beneficial impact on the energy management of public buildings. Literally all the proposals for “improvement” constitute cutting back the present requirements on the grounds that this would reduce the burden of regulation. The consultation’s cost-benefit analysis is also one-sided in counting the cost of doing DECs, but not their benefits in terms of triggering energy saving activity. Although it may be difficult to say categorically how much the presence of a DEC per se influences reductions in energy use, there has been a definitive study of all DECs lodged up to June 2012 which showed that those buildings which took DEC compliance seriously by renewing their DEC every year collectively achieved substantial energy savings.

The proposals in the consultation equally fly in the face of the government’s Open Data commitment “for the government to release data it holds, such as information on where money is spent and how well public services are performing … transparency isn’t just about access to data, but also making sure that it is released in an open, reusable format”. By removing the requirement to publish data on the energy used by public buildings, the proposals would take important data — whose publication the government itself predicted would create pressure to reduce energy use – out of the public domain. Citizens, academic researchers and journalists would no longer have any way of finding out, for example, whether public buildings generally were succeeding in becoming more energy efficient or whether vaunted ‘green’ buildings were living up to their promises.

It can be concluded that, in this age of austerity, the key question to be answered by this consultation is the following: if we continue with DECs would the cost of doing so be compensated by the benefit of reductions in public sector energy bills catalysed by the display of a DEC. Wider societal benefits, such as energy security and climate change mitigation, could be factored in or considered the icing on the cake, but let’s leave them out for now.

From this perspective, more important than any commitment to open data or theoretical value of public pressure would be actual evidence that DECs have indeed catalysed reductions in energy use. The original UK Statutory Instrument Explanatory Memorandum justified the annual renewal of DECs as cost effective against 10 year renewal by estimating the increased energy savings DECs would generate. Table 14 of that document estimates annual DECs to be more cost beneficial by £457m net present value and Annex C sets out all the reasons for why DECs are preferred to EPCs and why annual renewal is the most cost effective option.

“The appetite of organisations to embrace and prioritise energy management and efficiency can be fickle.”

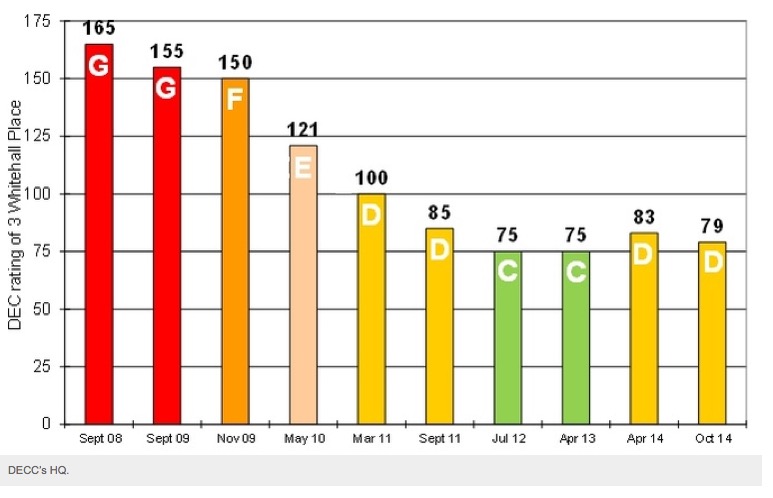

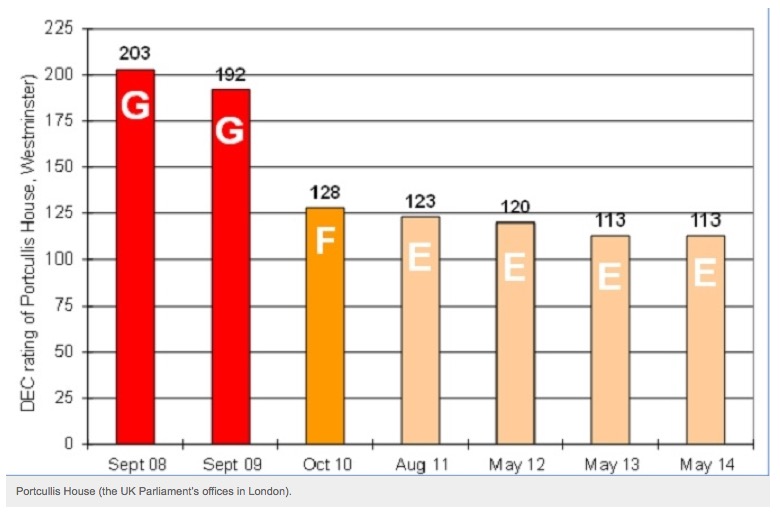

Although the consultation does not cite it, there is evidence that these predicted savings were, if anything, conservative. Below are graphics showing the operational energy performance of three rather pertinent buildings over the period 2008 – 2014: DECC’s HQ, Portcullis House (the UK Parliament’s offices in London) and DCLG’s offices in Birmingham. All three verify a halving of energy use, dwarfing the savings estimates. In each case, this has been achieved by bringing the buildings under operational control and then applying simple cost effective measures (not deep retrofits or fancy low carbon technologies). These exemplars demonstrate that huge energy savings are possible if the will is there to make the effort. The discipline of DECs holds the building operators to account and rewards their success by making it visible.

The clear message here is that DECs can support a culture which prioritises energy efficiency. Independent verification of actual savings is a key part of a narrative which demands that energy efficiency success is evidence based.

What might be done?

To achieve the full potential benefits of DECs, DCLG must invest a little in improving the DEC regime – up to now, since it was introduced in 2008, it has been neglected. Here are some suggestions for what might be done:

- Refresh the DEC benchmarks for energy consumption in particular types of building.

- Upgrade the Advisory Report which accompanies a DEC and lists improvement measures.

- Reintroduce site DECs for schools (and other ‘small’ multi-building sites) where the existing energy metering only exists at the site level – this would truly simplify the process, produce accurate (not pro rata) DECs and align with normal school energy management practices. Of course, where buildings are individually metered, a building DEC theoretically gives better granularity, but, at present, the benchmarks are designed for whole schools not classroom blocks, assembly halls, etc.

- Run a public information campaign to raise awareness of DECs.

- Use the Central Register to produce ‘official’ energy performance league tables for public buildings, creating reputational pressure and a healthy competition attitude.

- Allow independent parties to use all the data from all DECs on the Central Register to scrutinise the drivers of energy efficiency and make ‘unofficial’ peer group comparisons.

- Use the Central Register to identify overdue DEC renewals and to drive enforcement.

The appetite of organisations to embrace and prioritise energy management and efficiency can be fickle. Those with more energy intensive operations can generally be counted on to apply cost-effective measures, but the rest of us do not behave as the rational profit-maximisers of classical economic theory. In some parts of the US and for large commercial office buildings in Australia, evidence is emerging that robust and transparent reporting can motivate rapid improvements in operational energy efficiency, enhance property values, lower vacancy rates and increase yields. A building’s actual energy performance has become a status symbol, with a market value probably higher than would be justified by energy running cost savings alone. The alignment of operational energy efficiency with shareholder value in commercial property has created a virtuous circle between policy objectives and market forces. In both countries there are thriving networks and communities supporting each other and indulging in healthy competition[9]. Such a culture can be created in England and Wales around the promotion of DECs.

In my view, DECs are a valuable annual reporting discipline which verify actual performance, demonstrate what works and what does not when it comes to energy efficiency improvement measures and which can create a healthy competition attitude to incentivise better performance. Let’s not throw out the baby with the bath water.

It is a pity that you are not reproducing the impressive graphics for the improvements for the energy improvements from the three government buildings, referenced in the paragraph beginning “Although the consultation does not cite it…”

The fact that one of these vastly improved buildings is occupied by precisely the same Government Department that is seeking (despite achieving such substantial financial savings itself ) to abolish any requirements for energy monitoring , does suggest that this idiotic policy is being promoted by politicians far more interested in right-wing dogma than saving taxpayers’ money.

Mea culpa. You are quite right. It has been updated to include them.