Allison Asplin of Bloomberg News Energy Finance wrote the following post for Banking Energy. IT is an excellent article outlining the issues concerning the real estate industry and energy efficiency. This report was commissioned by Banking Energy, part of Consumer Energy Report.

Allison Asplin of Bloomberg News Energy Finance wrote the following post for Banking Energy. IT is an excellent article outlining the issues concerning the real estate industry and energy efficiency. This report was commissioned by Banking Energy, part of Consumer Energy Report.

Why Energy Efficiency and Buildings Don’t Mix

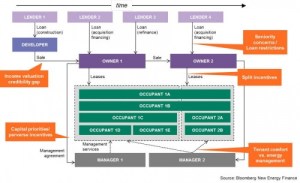

How does the real estate industry make energy efficiency decisions? And what part of the process is holding back adoption? Five main ‘friction points’ can slow or stop the momentum for energy efficiency adoption by the real estate industry.

Figure: Real Estate Industry Interfaces and Energy Efficiency ‘Friction Points’

Recent analyses by Bloomberg New Energy Finance suggest that opportunity exists for energy efficiency investment of $11 billion per year in US commercial real estate and $3 billion per year in multifamily. Nevertheless, conflicting incentives among stakeholders hinder energy efficiency investment in these segments. These stakeholders fall into five broad categories: developers, owners, occupants, lenders, and managers. At each interface between categories, ‘friction points’ arise, diminishing the impetus for energy efficiency.

The Developer-to-Owner Gap: Income Valuation and Credibility

Developers have a crucial role in determining a building’s future energy performance, since they make decisions about building design, including orientation, equipment, and materials. To many real estate industry participants, energy cost savings projections are unpredictable and unfamiliar, and therefore, not fully credible. This view prevents the value of energy efficiency upgrades from being fully reflected in a buyer’s building valuation.

The developer has incentive to invest in improvements that will credibly boost building net revenue. To the degree that energy savings projections lack credibility in the market, developers allocate funds to other building components – not energy efficiency.

The Owner-to-Lender Gap: Who’s on Top?

Most large commercial and multifamily buildings have mortgages in place, frequently interest-only loans that require the principal to roll over into a new loan at expiration. Energy efficiency financing structures – such as Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) loans, project loans, and on-bill finance – can trigger default under an existing mortgage by breaching lenders’ conditions regarding seniority and debt load

Leases and other off-balance-sheet structures can circumvent this problem by appearing as operating expenses rather than as liabilities on a building’s balance sheet, but recent regulatory movements may end this accounting practice. A debate between the US Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the International Accounting Standard Board (IASB) has brought into question the treatment of leases under US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). If IASB wins the debate and nearly all leases (and similar obligations) are brought onto the balance sheet, then these forms of energy efficiency finance will face the same obstacles as other junior forms of debt. Until FASB makes its final decision, owners will be wary of entering into financing arrangements that may unwind in the near future.

The Owner-to-Occupant Gap: The Buck Stops Where?

Perhaps the most widely discussed friction point is the interaction between owner and occupant. Much of the dialogue in the industry has focused on the so-called ‘split incentive,’ or the situation in which the owner pays for upfront capital costs, but energy savings from efficiency upgrades accrue to the occupant. The oft-prescribed solution to this problem is the ‘full service’ lease, in which the landlord pays for utilities as well as capital upgrades, theoretically incentivizing the landlord to invest in energy efficiency upgrades to reap the savings of a lower energy bill.

The reality of the situation is much more complex. A lease is a negotiated document, and depending on each party’s finances and appetite for risk, the responsibility for capital and operating costs can fall entirely to the landlord, entirely to the tenant, or be shared by both.

None of the five standard lease types addresses all the potential pitfalls of the landlord-tenant relationship.

The ideal lease structure for incentivizing energy efficiency investment must do two things: reward the landlord for providing capital, and hold the tenant accountable for its energy use. An efficiency-friendly green lease structure would include provisions that allow an owner to allocate upfront capital costs to the occupant, require ongoing quality control of systems and equipment, and mandate information exchanges between landlord and tenant.

The Owner-to-Manager Gap: Tough Decisions and Perverse Incentives

The friction between building owners and managers can come from both sides of the relationship. On one hand, a manager proposing energy efficiency projects may find these recommendations rejected by the owner. Energy efficiency projects must compete against a building’s (or portfolio’s) other capital needs and are usually passed over for more urgent projects.

On the other hand, an owner trying to improve energy performance can meet resistance from the manager. Property managers’ fees are usually calculated as a percentage of the building’s revenue. To the degree that energy costs are included in building income, higher energy costs mean higher fees for the manager. This compensation structure creates a perverse incentive for the manager to increase energy costs – or at least, not to pursue efficiency improvements. In reality, the potential revenue hit is small: a typical management fee is 1% or less. For sophisticated managers, the marketing value of an efficient building far outweighs the small potential fee impact. For less sophisticated managers, the perverse incentive can contribute to a laissez-faire attitude that stifles efficiency.

The Occupant-to-Manager Gap: The Customer is Always Right?

A final source of friction in the energy efficiency decision-making chain is the relationship between the occupant and the manager. The occupant-manager relationship, unlike the others described here, is generally not a contractual one; the two parties are linked by their individual contractual relationships with the owner. Nevertheless, their interaction plays a major part in the energy consumption of a building.

The manager’s most important job is to keep the occupant happy, and most occupant complaints relate to comfort. The manager’s actions in response to occupant complaints, such as temperature adjustments, can significantly increase energy consumption.

Additionally, many practices under the umbrella of ‘green building’ actually undermine energy efficiency, and certain efficiency measures impinge upon occupant comfort. Bringing additional fresh air into a building, for example, requires extra energy to heat, cool, or dehumidify air from outdoors. Occupancy sensors often prompt complaints that the lights turn off at inconvenient times, or that unlit spaces feel unsafe. Therefore, a manager’s efforts to ‘go green’ or cater to tenant comfort can come into direct conflict with efficiency.

This article summarizes an Insight Note, “The silent obstacles to energy efficiency in real estate,” recently published by Bloomberg New Energy Finance. The author can be reached directly at aasplin@bloomberg.net.